The following is the final in a 7-part series of posts to help all of us be there for those we love who are grieving, especially during the holiday season. The content is taken from my presentation, “How Not to (Unintentionally) Say Something Stupid: BE-ing With Those Who Are Suffering” © 2013. All rights reserved. Feel free to share/re-post, but please don’t swipe or present it without my permission.

We made it! We’ve covered some of the top barriers to BE-ing with others’ pain:

- Fear saying the wrong thing

- Feel the need to fix it

- Uncomfortable with pain and tears

- Uncomfortable with silence

Now we can cover the last:

- Fear not knowing what to say

I spend much of this presentation telling folks what NOT to say, encouraging them to say nothing but to just BE present. I talk about how to find a logical, theological, philosophical, emotional, and physical sense of grounding that will help them let go of the need to DO so they can simply BE.

But many miss the point, or aren’t quite ready for it, yet. They appear somewhat frustrated as they continue to insist I tell them what they CAN say. And I get it.

Pain can be terrifying. Being emotionally available with another’s vulnerability can bring out our biggest “oh crap!” fears. I’d rather do fractions that, since I missed the first 3 days on fractions in 3rd grade and never caught up, still gives me the hives!

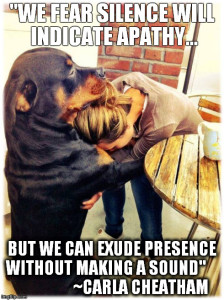

They still can’t quite get it that saying nothing verbally can be done with a sense of presence and grace and compassion that says far more than words ever could. In fact, presence alone can say far more since words aren’t there to get in the way!

They still can’t quite get it that saying nothing verbally can be done with a sense of presence and grace and compassion that says far more than words ever could. In fact, presence alone can say far more since words aren’t there to get in the way!

But I used training wheels as I learned to ride a bike. I used inflatable bumpers in the gutter when I was five. I learned under the supervision of more experienced professionals as a therapist, pastor, and chaplain until I was a little less green and a little more competent.

To protect myself and others from my novice skills, I find and use support. I got back up on my roller blades not long ago, at the tennis court where I could grab the fence rather than face plant until I get my strength and sense of balance beefed up a bit. And, I pay an accountant not only so I won’t have to take Benadryl for my math hives but also so I won’t make an innocent mistake and go to jail!

My main concern, and why I spend so little time on this part of the series, is that verbal training wheels run the risk of becoming addictive. They give us an out so that we feel we never have to learn this whole presence thing and, instead, hide under our verbal security blankets and leave those hurting out in the cold, untouched by true connection.

And then I find that all I’ve done is given folks a whole new list of pat phrases that will become just as damaging as those old, used-up, dry-as-dirt clichés that do nothing to touch someone’s pain.

So please, if you find yourself REALLY wanting to know what TO say, I ask that you stop for a moment and ask yourself why…what scares you? The answer may help you go a bit deeper in your ability with the art of BE-ing.

No number of slick, skilled, “perfect” words will be of any use if you aren’t settled within, and are using them to distance yourself from the other rather than convey that you are with them and they are not alone.

But again, I know that when we are first learning, some supports are helpful. So here are some phrases to consider if they would be helpful. Whatever you use, find what works for your voice and your personality. Pulling someone else’s words out can sound canned and fail to let someone else feel seen and heard. Find you, and share that. That is always the best gift you have to bring.

What TO Say:

I hear you. (Can be quietly repeated as they talk as much as they need, and they’ll likely talk more if not interrupted by anything you feel the need to say.)

Would you like to tell me about him/her?

Would you like to talk about it?

I wish I had answers. I’m sorry I don’t.

I can only imagine how hard this is.

You’re not alone. We’re with you, as much as you would like.

I love/care about you.

I trust you to make it through this, even when it feels like you can’t.

I am so sorry. (Why not, “…for your loss”?—A loved one who has died did not “pass” like gas; they are not “lost” so we don’t need to put their faces on milk cartons. Euphemisms can be another way of distancing from their pain. Don’t use them!)

Can I please __(mow the yard, do the *laundry, pick up the kids)__ for you? (*ALWAYS ASK FIRST so you do not accidentally mow down the wildflowers she planted that look like weeds or launder his smell out of his favorite shirt.)

I’m here.

That’s it. There may be others, but I think long and hard about using them. Even some of the above, I’m hesitant to suggest, because they can be used in a way that drives disconnection rather than fuel connection, as I once heard Brene’ Brown share. So please, use these carefully. Think them through. Talk about them with a friend and see what feels natural and helpful for you, from your mouth and heart.

And please, if you do just HAVE to offer them a Kleenex, make sure you tell them this isn’t code for “please stop crying”, but support for them to feel free to continue crying as long as they need without being distracted by snot and tears!

When we can extend the gift of true presence to another, it is priceless, and has absolutely NOTHING to do with our words. It is a very rare gift. But I’m hoping to change that. With your help, we can help each other learn how to BE with suffering in a way that brings comfort and healing, rather than isolation and more pain.

To close this series, I’ll leave you with the words of a talented colleague who shared the following. They are words of challenge for us all, professional and lay person alike. I give thanks to Karl Knox, Director of Bereavement at Gulfside Hospice & Pasco Palliative Care, for his words and the permission to share them:

“As much as it might be helpful for some professionals to have a few key phrases in their back pocket, I would tend look more closely at what drives us – in this profession – to want to try and ‘fix things‘ or ‘make things better.‘ I would look at what makes US uncomfortable personally.

For example, if someone is sobbing uncontrollably, are we tempted to try and ‘fix that’ because we’re personally uncomfortable with deep grief? Do we hand them a tissue and say ‘it’s going to be OK’ even when we know, in our hearts, that at this moment that’s not at all a certain thing?

Sitting with someone’s pain, without trying to intellectualize it with pat phrases, is an art….and a big part of that art is knowing yourself well enough to recognize when you’re actually trying to ‘get something’ from the person you’re working with (praise, thank you’s, a pat on the back). I believe people know when we’re being genuinely present with them, and when we’re trying to get them to make us feel better about our role as a professional.”

Peace,

Carla