Research indicates patients want to talk to their providers about their religious and spiritual (R/S) concerns, but that they most often do not get to do so (Williams, et al, 2011). The reasons behind why this doesn’t happen are many. The reasons why it is critical that spirituality be included in differential diagnosis and a focus of care for ALL disciplines are even more.

Research indicates patients want to talk to their providers about their religious and spiritual (R/S) concerns, but that they most often do not get to do so (Williams, et al, 2011). The reasons behind why this doesn’t happen are many. The reasons why it is critical that spirituality be included in differential diagnosis and a focus of care for ALL disciplines are even more.

It takes ALL of us to provide competent spiritual care that neither neglects nor abuses patients and families…and it’s easier than you may think!

This series will address that “Sweet Spot”–the perfect middle ground we can walk as we journey with others during medical or emotional crises and help them access their beliefs that help them find meaning, comfort, and peace. All members of the interdisciplinary team can, and must, be engaged in ethical and respectful spiritual and existential care for persons of all faiths, and no particular faith.

Next week, I’ll discuss more of the “Why?”, citing research, best practices, and making the case that quality spiritual care can greatly impact an organization’s financial bottom line. This week, I’ll jump straight into the “How?”.

When I speak, I often joke that when Oprah calls or I win the lottery, I’ll buy copies of Puchalski and Ferrell’s Making Healthcare Whole: Integrating Spirituality Into Patient Care (2010) for every healthcare worker in the country.

It is a terrific overview of the very issue I seek to address as they argue that all disciplines must be equipped to screen for and intervene when patients and families exhibit spiritual distress. Then they must coordinate care with a professional, clinically trained spiritual counselor to assess and treat those sources of distress.

To be clear, Puchalski and Ferrell come largely from the hospital setting, in which the ratio of chaplains to patients is very high. In other settings, such as hospice and palliative care organizations, where those ratios should be much lower (1/40 in hospice, for instance), best practices require the spiritual care counselor (SCC) be involved in the patient’s care from the very first days of admission, introducing spiritual care services and providing the clinical spiritual assessment and coordinating on-going plan of care interventions.

But that is not always the case. Some persons reject spiritual care services because they fear the very idea of a “pastor coming in and preaching” at them, which is NOT what qualified SCC’s do. Others have connections to their own faith community and do not feel the need for an SCC to be involved in their care, which research tells us is actually a dangerous proposition for the outcomes of care–details next week. Other times, an SCC simply isn’t available when spiritual distress is noted.

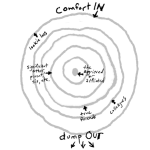

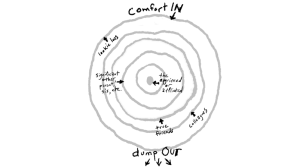

Regardless of the reasons, having nurses, physicians, social workers, certified nurses aides, etc. all feeling comfortable and competent to respond ethically to needs in the moment, until an SCC can be present, is a critical aspect of quality care.

One quick and easy tool provided by Puchalski (Puchalski and Romer, 2000) to screen for spiritual concerns is known as FICA. It stands for Faith and Belief, Importance, Community, and Address in Care or Action.

There are many ways these questions can be asked. Puchalski’s suggestions for ways of asking the questions may be found on the G-Wish website, here.

Below are ways that I train healthcare staff to ask the FICA questions. Over the years of my practice with patients and families, I’ve found the approach modeled below may increase how comfortable and safe patients feel answering honestly. Not only does it make for a gentler approach to them, it also helps ensure I gain the most accurate information possible, for the benefit of both them and the team navigating their care.

F- Is there any particular faith tradition in which you were raised?

Far better than “What church do you go to?”, which assumes they attend services and assumes they are Christian, the open language indicates acceptance if they answer is “No” or if they are of another faith.

It also can place persons less on guard because, many persons who are sick or have moved to be near family as they age, or are just busy with their every day lives can feel guilty or even ashamed to admit if they do not attend services and fear judgment by the persons providing their care. It’s scary to “disappoint” the people bringing you the good drugs, the therapies, the supplies, the legal and logistical support, etc. Asking if their parents raised them in a tradition can take the pressure off of them, a bit, if they do not attend.

Lastly, what happens when you ask someone the beginning of the story? They will tell you the rest. In this one answer, persons can explain their spiritual journey in 60 second, “I was raised ______, then when I was a teenager all my friends went to _______, then I went to college and, well, you know, that was college, and then I married and he was _______, then we had a falling out with the minister so we went to…”

As they tell us their journey, we’re listening for whether they are spiritual, religious, both, or neither. They may have felt rejected or disillusioned with organized religion and have picked up some spiritual baggage which they may need to address. They may have old images from the faith of their childhood that can return during times of distress and fear, at the end of life for instance.

So we listen for landmines. We listen for spiritual strengths. We listen for the beliefs of other family members that may either support or be in conflict with the patient’s views. We listen for the language that they use to discuss their faith. We are open to hearing if they are non-theists (atheists, agnostics, humanists, etc.) and switch our language to more existential (meaning, love, connection, etc.) rather than religious words to meet them where they are.

Not bad for one question!

I- Which of your current beliefs/ideologies are most valuable or helpful to you right now? What brings you the most comfort?

Asking someone how important their faith is to them can leave persons feeling judged even before they answer if their religion isn’t of particular importance. But asking what is helping them can open up the possibilities to include a favorite rock song that keeps them going or art that speaks to them of peace or a pet that gives them connection. These all can be used to support their spiritual/existential well-being. It doesn’t always have to be a prayer or ritual. We are multi-dimensional creatures, so it’s no surprise if we connect with a deity in multiple ways.

C- If there is a crisis at 2 a.m., whom do you want me to call to come be with you and your family?

For some people, their clergy may be their primary source of support. But for others, it may be another member of their faith community, or a best friend or neighbor. We mustn’t assume.

For one woman who was a conservative Catholic, the answer was her Jewish accountant. He had started as a young, wet-behind the ears CPA when she and her husband started business 30 years before. She trusted him completely and he always watched out for her best interests. They had a spiritual bond that ran very deep. So when I DID need to call on him at 2am, he came and said prayers in Hebrew and English, went through the Rosary with her, and sang Amazing Grace while I sat in humbled silence in the corner and witnessed a beautiful moment of spiritual care unfold.

A- What do we need to know about how your particular culture and beliefs/ideologies will influence your decisions, or to which we should be respectful?

We do not want to offend. We want to provide ethical and respectful care. But if we do not directly ask, we may never know what that looks like for them. Merely asking the question can indicate to them how deeply we wish to honor them, their culture, their faith, their needs, and that they will not be judged by us for whatever they need. Asking ahead of time has saved my kiester on more than one occasion and, more importantly, allowed me to provide competent care.

I’ll tell you a story about that in the midst of this series, when a young CNA knew to ask a question that completely changed the outcome, and quality, of a case.

For now, I hope something of this has been helpful. I look forward to sharing more ideas for ways that all of us can be involved in spiritual care that is respectful, ethical, and makes a difference, and is far easier than you might imagine!

Peace…

Williams, J., Meltzer, D., Arora, V., Chung, G., & Curlin, F. (2011). Attention to Inpatients’ Religious and Spiritual Concerns: Predictors and Association with Patient Satisfaction. Journal of General Internal Medicine. DOI:10.1007/s11606-011-1781-y

About Rev. Dr. Carla Cheatham:

After a career in social services, with an MA in Psychology and certification in crisis counseling, Carla received her MDiv. and PhD. in Health & Kinesiology and began serving faith communities. For almost a decade, she has worked as a spiritual counselor in healthcare, primarily for hospice.

After a career in social services, with an MA in Psychology and certification in crisis counseling, Carla received her MDiv. and PhD. in Health & Kinesiology and began serving faith communities. For almost a decade, she has worked as a spiritual counselor in healthcare, primarily for hospice.

After realizing many lacked supportive education in multi-faith spiritual care, Carla and her colleagues created the SCIE (“sky”) curriculum, which expanded to include boundary training and presentations in a multitude of areas.

Carla has taken stories from the curriculum and published them as a book of stories called Hospice Whispers: Stories of Life, available here or through Amazon. The Grief Companion Guide to Hospice Whispers designed for both individuals and groups, is set to publish later this Spring. She is also writing her second book on the art of presence with those who are suffering.

Follow Carla’s writings on her blog at http://carlacheatham.com/CCCG_SiteRevamp/carlas-blog/ and through Hospice Times at http://www.hospicetimes.com/index.php/category/guest-articles/carla-cheatham/